Politics in India Dynamic Governance

The Grand Arena of Indian Democracy

The landscape of politics in India represents one of the most complex, vibrant, and consequential democratic experiments in human history. Governing a nation of over 1.4 billion people, encompassing staggering linguistic, religious, and cultural diversity, requires a political system of immense flexibility and resilience. The study of politics in India is not merely an academic pursuit; it is an ongoing narrative of power negotiation, ideological contestation, and social transformation.

From the Himalayan north to the tropical south, politics in India operates at multiple, interconnected levels: the national parliament in New Delhi, the 28 state legislative assemblies, and the countless panchayats and municipalities at the grassroots. This multi-tiered structure ensures that political engagement permeates every layer of society, making politics in India a truly mass phenomenon.

The foundation of modern politics in India was laid with the adoption of its Constitution in 1950, which established a sovereign, socialist, secular, and democratic republic. This document provided the rulebook for a parliamentary system of governance, guaranteeing fundamental rights and instituting a framework for social justice.

The subsequent decades of politics in India have seen the system evolve from the one-party dominance of the Indian National Congress to a period of volatile coalition governments, and recently, towards a re-assertion of single-party majority rule under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Throughout these phases, the core institutions—the Election Commission, the judiciary, and a free press—have played critical roles in maintaining democratic continuity, even amidst severe stress and periodic crises.

See more about viral news for games at Pausslot Online Gaming Platform

Understanding contemporary politics in India requires an appreciation of several core dynamics: the intense competition between national and regional parties, the central role of identity (caste, religion, language) in electoral mobilization, the evolving economic agenda from state-led socialism to liberalization, and the growing influence of technology and media on political discourse. As India’s global stature rises, the outcomes of its internal political processes carry significant implications for international geopolitics, economic markets, and democratic ideals worldwide. This article delves into these multifaceted dimensions to provide a comprehensive overview of the forces that define politics in India today.

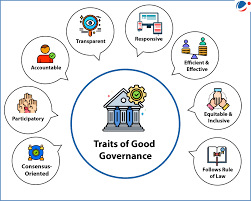

The Constitutional Framework and Structure of Governance

The machinery of politics in India operates within a meticulously designed constitutional framework that blends elements from various global models while retaining unique Indian characteristics. The Constitution establishes a federal structure with a strong unitary bias, meaning that while states have significant legislative and executive powers, the Union Government retains overriding authority in critical areas, especially during emergencies. This distribution of powers is a constant source of negotiation and, at times, conflict within politics in India, often pitting state governments against the central authority in New Delhi. The three pillars of the state—the Legislature, Executive, and Judiciary—are designed to maintain a system of checks and balances, though the balance of power has shifted dynamically over the decades.

The Parliament, consisting of the Lok Sabha (House of the People) and the Rajya Sabha (Council of States), is the supreme legislative body. The Lok Sabha, whose members are directly elected by the people, is the more powerful house, as the party or coalition commanding a majority here forms the government. The Prime Minister, the effective head of government, emerges from this house.

The Rajya Sabha represents the states, providing a forum for federal considerations. The legislative process in politics in India is often a theater of fierce debate, partisan maneuvering, and, regrettably, frequent disruption, reflecting the intense pressures of a competitive democracy. The Executive, headed by the President (the ceremonial head) and the Prime Minister (the real executive), is responsible for implementing laws and administering the country.

An exceptionally powerful feature of politics in India is its independent judiciary, with the Supreme Court at its apex. The judiciary has repeatedly acted as a guardian of the Constitution and fundamental rights, often venturing into areas traditionally considered the domain of the executive through judicial activism and Public Interest Litigation (PIL). Landmark judgments on environmental protection, electoral reforms, and personal liberties have profoundly shaped policy and public life. The ongoing tussle between the judiciary and the executive over judicial appointments and the scope of judicial review remains a significant subplot in the story of politics in India, highlighting the constant evolution of institutional relationships within the democratic framework.

The Evolution of the Party System: From Congress Dominance to BJP Ascendancy

The party system is the dynamic engine of politics in India, and its transformation over seven decades tells the story of the nation’s changing social and ideological landscape. For the first thirty years after independence, the Indian National Congress functioned as a dominant “catch-all” party, led by the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. It embodied a centrist, secular, and socialist consensus, successfully managing a diverse coalition of interests. However, the decline of the “Congress system” began in the late 1960s, accelerated by internal splits, the imposition of the Emergency (1975-77), and the rise of alternative political aspirations among regional and caste-based groups.

The 1990s marked a pivotal turning point in politics in India, characterized by the end of single-party majorities and the dawn of the coalition era. Two major events reshaped the political universe: the implementation of the Mandal Commission’s recommendations, which mandated reservations for Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, which mobilized Hindu nationalism. This period saw the rise of powerful regional parties like the Samajwadi Party (SP) and Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) in the north, and the Dravidian parties in the south, alongside the maturation of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as a national force. Governance depended on fragile alliances, making consensus-building and compromise essential arts in politics in India.

The contemporary phase, beginning around 2014, signals a new epoch characterized by the resurgence of a dominant national party. Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the BJP has secured commanding majorities in the 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections, marking a shift away from coalition dependency at the centre. This has been achieved through a powerful combination of Hindu nationalist ideology, a personalized leadership cult, a formidable electoral machine, and a narrative focused on development, national security, and cultural reassertion.

The Congress, meanwhile, has suffered a historic decline, struggling to redefine its ideological purpose and organizational vitality. This current landscape of politics in India presents a paradox of national-level dominance by one party coexisting with robust, often defiant, regional party rule in many states.

The Central Role of Identity: Caste, Religion, and Language

Perhaps no other democracy in the world is as profoundly shaped by social identity as politics in India. Caste, despite its formal abolition, remains the most pervasive and intricate factor influencing electoral behavior, party formation, and policy-making. Political parties meticulously calculate caste equations in selecting candidates and crafting manifestos.

The empowerment of lower and middle castes through affirmative action (reservation) and political mobilization has fundamentally altered power structures, dismantling the historical monopoly of upper castes. Parties like the BSP were built explicitly on Dalit assertion, while others like the SP and Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) have championed OBC interests. The BJP has skillfully navigated this terrain by building a broad social coalition that includes upper castes, sections of OBCs, and non-dominant Dalit groups under the umbrella of Hindu unity.

Religion is another potent and deeply contentious force in politics in India. The rise of the BJP is inextricably linked to the ideology of Hindutva, which advocates for the recognition of India’s Hindu civilizational heritage and, in its more assertive forms, for a Hindu-first national identity.

This has sparked an intense and ongoing ideological battle with the principle of secularism enshrined in the Constitution. Flashpoints like the Babri Masjid demolition (1992), the 2002 Gujarat riots, the enactment of the Citizenship Amendment Act (2019), and the construction of the Ram Temple in Ayodhya (2024) are not isolated events but chapters in this continuous struggle to define the nation’s soul. This religious-nationalist mobilization has reconfigured voter alignments and created new majoritarian political possibilities.

Linguistic and regional identities further complicate the mosaic. The linguistic reorganization of states in the 1950s and 1960s created powerful sub-national political units. Regional parties in states like Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, Andhra Pradesh, and Punjab fiercely protect their linguistic and cultural distinctiveness, often resisting what they perceive as homogenizing pressures from the Hindi-speaking north. Demands for greater financial autonomy and control over resources are constant themes in Centre-State relations. Thus, a successful national strategy in politics in India must adeptly manage this complex calculus of caste, religion, and region, a challenge that makes Indian elections a fascinating study in sociological engineering.

Federalism in Practice: The Centre-State Dynamic

The federal nature of politics in India is a defining feature, where a powerful Union government coexists with constitutionally strong states. This relationship is dynamic, oscillating between cooperation and conflict. The constitutional division of powers is outlined in three lists: the Union List (subjects like defense, foreign affairs), the State List (subjects like police, agriculture), and the Concurrent List (subjects like education, marriage) where both can legislate. However, in case of a conflict, the union law prevails. This structure inherently creates a fertile ground for disputes over jurisdiction, which are a staple of politics in India.

Finance is a perennial flashpoint in federal relations. The central government controls the major levers of revenue collection (like income tax, customs duties), which it then shares with the states as per the recommendations of a Finance Commission constituted every five years. States frequently complain of inadequate devolution, unfunded mandates (where the centre announces schemes states must pay for), and delays in disbursing funds. The introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), while a landmark reform for economic integration, has also led to new tensions within the GST Council over tax rates and compensation. The fiscal health of states significantly impacts their ability to deliver services, making this financial negotiation a core aspect of practical governance.

The role of the Governor, the centre’s appointed representative in each state, and the use of central investigative agencies have become highly politicized instruments. Opposition-ruled states routinely accuse Governors of partisanship—withholding assent to bills indefinitely, interfering in university administrations, and making politically charged statements. Simultaneously, investigations by the Enforcement Directorate (ED) and Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) into politicians of opposition parties are seen by critics as a tool to undermine state governments and coerce political alignment. These actions test the boundaries of constitutional propriety and are central to contemporary debates about the erosion of federal principles in politics in India, even as cooperative forums like the NITI Aayog strive to foster partnership.

The Electoral Process: Scale, Strategy, and Democracy’s Festival

Elections are the magnificent, chaotic heartbeat of politics in India. Conducted by the independent Election Commission of India (ECI), they are a logistical marvel, involving nearly a billion eligible voters, millions of polling officials, and over a million polling stations. The general elections, held every five years, are the world’s largest democratic exercise, but state assembly elections occur almost continuously, ensuring that the campaign machine is never fully at rest. The conduct of free and fair polls, despite instances of violence and malpractice, remains a cornerstone of India’s democratic credibility, a feat that draws global attention and admiration.

Electoral strategy in politics in India is a sophisticated science. It involves intricate “social engineering”—forging coalitions of caste and community groups. Candidates are selected based on their ability to deliver the votes of their specific community or sub-caste. Campaigning has evolved from mass rallies and door-to-door canvassing to a data-driven enterprise. Parties now use voter profiling, social media micro-targeting, and sophisticated messaging apps to reach different demographic segments. The use of money, or “black money,” to finance campaigns and influence voters remains a systemic challenge, though measures like the now-invalidated Electoral Bonds scheme were attempts to formalize political funding.

The issues that dominate elections vary across regions and levels. National elections might be fought on themes of leadership, national security, and macroeconomic performance, while state elections hinge on local grievances like farmer distress, electricity tariffs, or the performance of state welfare schemes. The personal charisma of leaders—from Narendra Modi’s oratory to regional stalwarts like Mamata Banerjee’s street-fighter image—plays an enormous role. The verdict of the Indian electorate has repeatedly demonstrated its unpredictability and wisdom, throwing out incumbents perceived as corrupt or incompetent, and making the outcome of any election the ultimate, authoritative event in politics in India.

Economic Policymaking and Development Politics

The economic ideology of the state has undergone a radical transformation, profoundly influencing politics in India. For decades, a socialist model emphasizing state control, import substitution, and heavy industry defined the “License Raj.” This began to change in 1991 with a profound economic crisis that triggered sweeping liberalization reforms, opening India to global trade and investment. This shift from a controlled to a market-oriented economy created new business elites, expanded the middle class, and altered the sources of political funding and patronage. The debate between the virtues of state-led welfare and market-driven growth continues to be a central fault line.

Today, economic governance is a primary battleground. The ruling government champions its record on building physical infrastructure (highways, ports, airports), implementing a national Goods and Services Tax (GST), and pushing digital financial inclusion through schemes like the Jan Dhan Yojana. It promotes initiatives like “Make in India” and Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes to boost manufacturing. The opposition, however, counters by highlighting persistent challenges: high unemployment, especially among youth, agrarian distress leading to farmer protests, rising inequality, and inflation affecting the common household. The management of the economy is thus a key metric on which governments are judged electorally.

Welfare politics has become a massive enterprise. Both central and state governments run extensive subsidy and direct benefit transfer (DBT) programs, providing free or highly subsidized food, cooking gas, electricity, water, and cash support to hundreds of millions. While credited with reducing poverty and providing a social safety net, these schemes are also criticized for fostering dependency and being used as clientelistic tools for electoral gain. The politics of reservation (affirmative action) has also expanded from education and government jobs to demands for quotas in private sector and promotions, reflecting the intense competition for scarce opportunities in a growing but uneven economy, making economic distribution a core conflict in politics in India.

Foreign Policy and National Security as Political Domains

While traditionally an elite preserve, foreign policy and national security have been democratized and politicized like never before in contemporary politics in India. The government’s handling of border standoffs, most notably with China in Ladakh, and its stance on cross-border terrorism from Pakistan are subjects of intense public debate and partisan scoring. Military actions like the “surgical strikes” (2016) and “Balakot airstrike” (2019) were leveraged as powerful symbols of a resolute, new India, effectively blurring the lines between security strategy and domestic political messaging. This “muscular” posture has significant domestic political appeal.

India’s evolving position in the global order is also a matter of political discourse. The pursuit of strategic autonomy, navigating relationships with the United States, Russia, and other major powers, and leadership aspirations in forums like the G20 and Global South are portrayed as achievements of strong, visionary leadership. The diaspora, a significant source of remittances and soft power, is also actively courted as a political constituency. However, foreign policy decisions, such as the continuing dependence on Russian defense equipment amidst the Ukraine war, can also attract criticism from opponents who question the long-term strategic costs.

National security infrastructure and reforms are part of the governance narrative. The creation of the post of Chief of Defence Staff (CDS), the push for “Atmanirbhar Bharat” (self-reliance) in defense manufacturing, and the modernization of armed forces involve massive budgetary allocations and bureaucratic decisions. The politics of internal security, particularly in regions like Jammu & Kashmir and the Northeast, involves complex negotiations between military, developmental, and political approaches. How these security challenges are managed impacts not just India’s international standing but also the ruling party’s image as a guarantor of national strength and integrity, making it a critical component of today’s politics in India.

The Future Trajectory: Challenges and Continuity

The future of politics in India will be shaped by its ability to navigate several formidable challenges. The first is institutional integrity. Concerns about the erosion of independence in key institutions—the judiciary, election commission, investigative agencies, and the media—pose a long-term threat to democratic accountability. The second is social cohesion. The deepening of majoritarian impulses and the marginalization of minority communities risk creating lasting social fractures and undermining the pluralistic foundation of the republic. Managing diversity while fostering a shared national identity remains the central dilemma.

Economic challenges will continue to drive political outcomes. Generating sufficient employment for a massive young population, transitioning to a green economy, and ensuring that growth benefits are widely shared are imperative for stability. The quality of public services in health and education will determine human capital development. Furthermore, the impact of technology—from social media’s role in spreading disinformation to the use of surveillance tools—will redefine political campaigning and citizen-state interactions, presenting new regulatory and ethical quandaries.

Despite these challenges, the resilience of Indian democracy should not be underestimated. Its greatest strengths lie in the political awakening of its entire populace, the vigilance of its civil society and media, and the deep-rooted belief in the electoral process among its citizens. The politics in India is likely to remain a vibrant, noisy, and contested arena where multiple visions of the nation’s future—as a Hindu homeland, a secular republic, a global economic power, or a federation of strong states—will continue to compete. This very contestation, for all its messiness, is the hallmark of a living democracy, ensuring that the story of politics in India remains one of the world’s most compelling political narratives.